Modern Thought and Catholicism

In addition to being an innovative painter, sculptor, and printmaker, Gauguin was also a dedicated writer who composed art criticism, letters, a fictionalized journal, and essays about Polynesian culture. He wrote this 92-page manuscript concerning philosophy, religion, and society in 1902, when he was living in the small town of Atuona, on the island of Hiva Oa in the Marquesas Islands.

For this text, Gauguin considered the relationship of similar stories across a number of global religions, ranging from Christianity and Buddhism to Polynesian theology. He meditated on the mysteries of creation, the place of humankind on earth, and the origins of the soul, and he offered a critique of the social institutions of the Catholic Church and of marriage.

Gauguin transcribed large portions of this work from a manuscript he wrote previously in Tahiti in 1897–1898, just before beginning his painting Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (see image). His return to this essay in 1902 reflects his desire to help promote this painting in France, where he hoped it would be acquired for the French National Collections. Gauguin also intended to publish his treatise in Paris, but he died in 1903 without realizing that goal.

On the first page of this manuscript, Gauguin wrote a dedication to the French poet Charles Morice, who had helped the artist edit and publish his journal Noa Noa. Gauguin hoped Morice would publish this work as well, but it never reached Paris. After the artist’s death in 1903, some of Gauguin’s belongings were put up for sale in Tahiti, and this manuscript was sold to Alexandre Drollet in Papeete. Claude Rivière, an art critic for La France magazine in New York, then acquired it from Drollet in Tahiti by 1927.

From Rivière the manuscript went to a private collection in Los Angeles and then to a book dealer, who sold it in 1947 to the film star Vincent Price, an avid collector of modern art. Price considered donating the manuscript to museums in Los Angeles or Chicago; however, Price was both a native St. Louisan and a friend of Perry T. Rathbone, then director of the Saint Louis Art Museum. Price gifted the manuscript to the Museum in 1948 in honor of his parents. He later recalled that he bought it “because it was a rare statement by a rare and controversial artist.”

Gauguin’s thoughts on Catholicism run throughout the manuscript. He pointedly critiqued the church’s control over women: “Woman, who after all is our mother our daughter, our sister, has the right to make her own living . . has the right to love whomever she pleases [. . .] has the right to give birth with the possibility of raising her own child.” He also criticized Christian marriage and its practice of regarding as legitimate only children born in wedlock: “The very institution of marriage creates two classes of children, those who must be raised and those the law, our habits allow, or even order us to abandon.”

Gauguin’s concern with these issues was derived partly from personal circumstances: he was not divorced from his Danish wife, Mette, and he was not married to Marquesan Vaeoho Marie-Rose, with whom he had a daughter in 1902. But Gauguin’s interest in these issues was long-standing. His maternal grandmother, Flora Tristan (1803–1844; see image), was a utopian socialist thinker, a writer and traveler, an early feminist, and a political activist who lived a very unconventional life. He kept her books with him while living in Polynesia and respected her work to extend the rights of working-class women under French law. Her thinking inspired many of the comments about women’s repressed position in modern society in this manuscript.

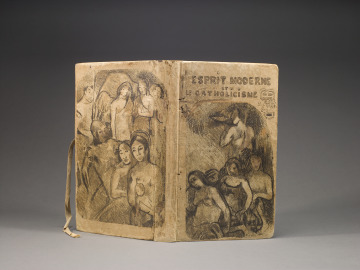

In moving from Tahiti to the Marquesas in 1901, Gauguin sought to explore a place even less influenced by European modernity (see image). In some ways he succeeded: many aspects of Marquesan indigenous art, culture, and religion had survived the arrival of French colonialists. In the commune Atuona, he lived within a mix of French and Marquesan spiritual practices, although the Catholic Church played a large part in the governance of daily life. The cover of his manuscript speaks to this hybrid of cultures; it features both a French fleur-de-lis, at top left, and a Marquesan tiki, at top right.

Gauguin challenged the government to take action against the impositions of Catholicism: “Without attacking freedom, in the name of this very freedom, would the State not have the right to suppress the Church totally?” He advocated that individuals resist the church if the government will not: “Yet what the State doesn’t do, common sense, the world’s greatest revolutionary, shall do.” He also blamed the “the troubles we see in the colonies” on religious conflicts. In this text, Gauguin promoted an ideal of religious freedom and a personal fusion of beliefs and practices from a range of world religions without overtly condemning the colonizing efforts that brought and protected the Catholic missions in the first place.

In this manuscript Gauguin built on his long-standing interest in spiritualism and comparative religion. The artist was inspired both by the writings of French philosopher Édouard Schuré, such as the Grand Initiates (1889) and by the English spiritualist Gerald Massey, who wrote extensively on the origins and evolution of religions. In Tahiti Gauguin read a translation of Massey’s The Natural Genesis (1883) and copied passages into his first draft of this manuscript in 1897.

Gauguin sought parallels between world religions, including Christianity, Buddhism, the religion of ancient Egypt, and Polynesian theology. He accepted that all religions shared common truths based on similar stories. From Massey’s The Natural Genesis, he copied an emblem of Jesus and Horus, the ancient Egyptian god of the sky, standing on a crocodile and holding a fish. This Gnostic sign is used to symbolize the fusion of Christian and ancient Egyptian traditions (see image).

Gauguin was also drawn to parallels he perceived between Jesus and Buddha, writing: “It must also be said, Christ understood present life on earth as but a preamble, a transitory because temporary stage of life [. . .] this same understanding was already formulated by the Buddha when he conceived of life in its entirety as different, successive states of being ultimately leading to Nirvana as the final stage existing in the infinite.” Gauguin did not seek to replace or reject Christian-based spirituality in this essay, but rather to expand its scope by combining it with aspects of global religions, creating in his view a religious perspective that was better suited to living in a diverse world in the modern era.

Gauguin created two drawings for the manuscript cover that relate thematically to many of his painted works of 1902 (see comparative works below) that depict for example the birth of Jesus, and a gathering of Marquesans accompanied by a French nun from the nearby Mission. The front of the manuscript shows figures leaning in to assist a woman after childbirth, a scene not usually represented in Christian art. The standing male bears the type of platter used at a mau, or commemorative feast, such as the celebration of a child’s birth in the Marquesas. On the back, Polynesian angels attend the event. A halo designates a Polynesian virgin holding the child and a man, perhaps the artist, observes the scene from upper left.

These illustrations are transfer drawings that Gauguin pasted to the cover. This technique involves layering paper on top of another already coated in ink. The artist then draws on the blank sheet and lifts it to reveal the image, which has been transferred to the reverse surface of the paper.

On the inner cover, Gauguin pasted two of his woodblock prints. One suggests the human life cycle, displayed beneath the words “Be in love and you will be happy.” On the back inner cover, which Gauguin inscribed with the phrase “Lost paradise,” the print invokes the Garden of Eden, with a primordial Eve shown reaching toward the fruit of a tree.

We wish to acknowledge Elizabeth C. Childs for her intensive scholarship on this manuscript, and her initiative in making this presentation possible.

Transcription and Introductory Texts

Elizabeth C. Childs, Etta and Mark Steinberg Professor of Modern Art History, Washington University in St. Louis

Translation

Stamos Metzidakis, Professor Emeritus, Romance Languages and Literatures, Washington University in St. Louis

Project team at the Saint Louis Art Museum

Curatorial

Elizabeth Wyckoff, Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs

Simon Kelly, Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art

Hannah Wier, Research Assistant

Abigail Yoder, Research Assistant

Digital Platform Development

Chad Curtis, Head of Digital Platforms

Bryan Wiebeck, Web Developer

Conservation

L. H. Shockey, Director of Conservation

Sophie Barbisan, Associate Conservator

Nancy Heugh, Conservator (Retired)

Richard C. Baker, Independent Book Conservator, St. Louis

Noah Smutz, Independent Book Conservator, St. Louis

Photography

Cathryn Gowan, Head of Digital Assets

Ann Aurbach, Photography Manager

Janeshae Henderson, Digital Imaging Specialist

-

Help with Document Viewer

Select the transcription and translation icons to reveal a right-side panel. View the manuscript in full screen to maximize space for side panels and zooming.

Select the magnifying glass icon to open the left-side search panel. English and French languages are supported. Phrases must be wrapped in quotation marks. Delete the content of the search field to clear results.